Now that the “nuclear option” has been deployed in the United States Senate, many observers have begun wondering what might be the fallout from such a move.

First, a little background may put the ‘change in the rules of the Senate game’ in context. During the first 128 years of the U.S. Senate, it only took one senator to bring the floor proceedings to a halt through the practice of the filibuster.

Originally, the idea of a filibuster didn’t exist in the upper chamber until a rules change occurred in 1806, when the Senate dispensed with a parliamentary procedure to bring debate to a close and begin a final vote on a measure. By dispensing with this procedural way to end debate, most scholars have argued that while the possibility of filibusters was opened up, the Senate never conscientiously decided on having unlimited debate.

The first filibuster, however, didn’t occur until the 1840s, when Henry Clay sought to bring debate to a close on the controversial charter for the Second Bank of the United States. In attempting to bring back what the Senate had earlier dismissed, Clay was confronted with what has become the norm of filibustering: the threat to filibuster.

The minority then used the weapon of the filibuster more often in the late 1800s, since it would only take one senator to bring things to a standstill in the chamber. But in 1917, with the United States on the edge of entering World War I, a small minority of isolationist senators halted the congressional declaration of war, leading President Woodrow Wilson to call for filibuster reform against the “little group of willful men.”

This reform led to Rule XXII (22) in 1917, which allowed for invoking cloture, or limiting debate to move to a final vote, with the approval of two-thirds of all senators. The first cloture vote was to end a filibuster against the Treaty of Versailles.

The filibuster remained, however, an effective tool for a band of minority senators, even when they were in the majority. Southern Democrats, seeking to kill various attempts at civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s, used the filibuster and the requirement of 67 senators to invoke cloture as a method to halt legislation that would strike at the South’s segregationist practices.

Most notable was the 24 hour, 18 minute marathon conducted by then-Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond against the 1957 Civil Rights Act. Even though the bill would eventually pass the chamber following Thurmond’s talk-a-thon, the South Carolinian still holds the record for standing and talking on the U.S. Senate floor.

In 1975, another effort at reforming the filibuster was instituted by changing the cloture rules, this time reducing from 67 to 60 (or three-fifths) of the 100 senators to invoke an end to debate.

So the great outcry of invoking the “nuclear option” in changing the rules, while somewhat of a surprise in timing, isn’t been unheard of in the Senate’s past.

What is surprising is the evolution of the cooling “saucer” to the hot cup of the House of Representatives that the Senate was to serve. Part of this has to do with the continuing movement of the parties to opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. Much has been written about the polarization in the House, but the Senate is seeing its own infestation of ideological divergence.

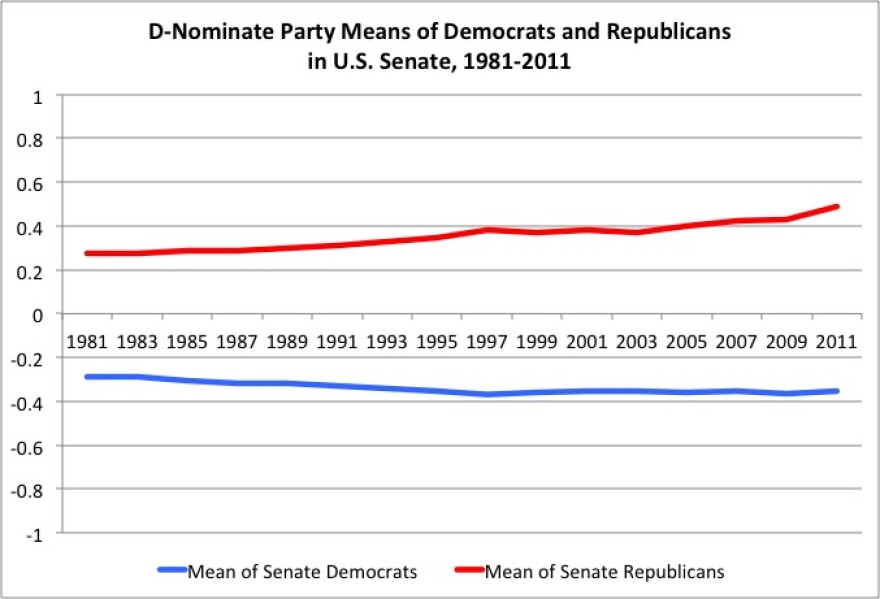

In going back to 1981 and using a commonly accepted measurement of ideology among members of Congress, the means of each party in the U.S. Senate has moved further apart over time. The lower the score (moving towards -1), the more liberal a score one would have, while the higher the score (moving towards +1) would indicate a more conservative score.

While the Senate Democratic Caucus has move slightly out of the moderate range into a liberal range, it has been the Senate Republican Conference (like its brethren in the House) that have become much more conservative.

But looking at both the most liberal and most conservative members of both Senate party groups, one finds the most conservative Republican now hitting against the magic +1 score, while the mixing of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats are now truly breaking into their own parts of the scale.

From 1981 until 1995, the most conservative Democrat was more conservative than the most liberal Republican; however, since 2005, the most conservative Democrat is now more liberal than the most liberal Republican.

This, along with the fact that the numbers in the middle of conservative Democrats and liberal/moderate Republicans have shrunk considerably from 1981 to 2011, means that there is no more middle of the upper chamber to perhaps bridge between the two polar extremes—even if the extremes were willing to talk to each other.

This most recent change in the Senate’s rules isn’t that unheard of, but the fallout from an increasingly radioactive body may mean more future detonations in the upper chamber of Congress.