North Carolina regulators next month will assign risk ratings to Duke Energy’s coal ash storage sites around the state. The ratings determine how and when the ash will be cleaned up. But what exactly does “cleanup” mean? There’s a big debate.

A few weeks ago, a state judge in Raleigh ordered Duke Energy to remove coal ash from three plants in eastern North Carolina. The order was in response to a suit filed by the Southern Environmental Law Center. Frank Holleman is a lawyer for the group.

“We hope and expect that DEQ will pay attention to what the judge has said and also to what the public is saying now, and that these sites will be cleaned up without any more hitches and these rivers and these communities will be protected,” Holleman said.

The next day, a DEQ spokeswoman asked WFAE for a correction on Holleman’s characterization, saying: “This implies that the coal ash ponds would not be cleaned up without the judge’s order.” She said the Coal Ash Management Act requires Duke to close all its North Carolina coal ash sites.

True, the 2014 state law does that. But there’s a wide gap between what she means and Holleman’s definition: “By cleanup, we mean remove the ash from these unlined riverfront pits, and move the ash to safe, dry, lined storage away from the river, or it could be recycled for concrete.”

Coal ash is what’s left after burning coal. It contains heavy metals and other toxins that can cause cancer. For DEQ and Duke Energy, cleanup means any method of reducing the risks of coal ash – whether it’s removal or leaving ash where it is.

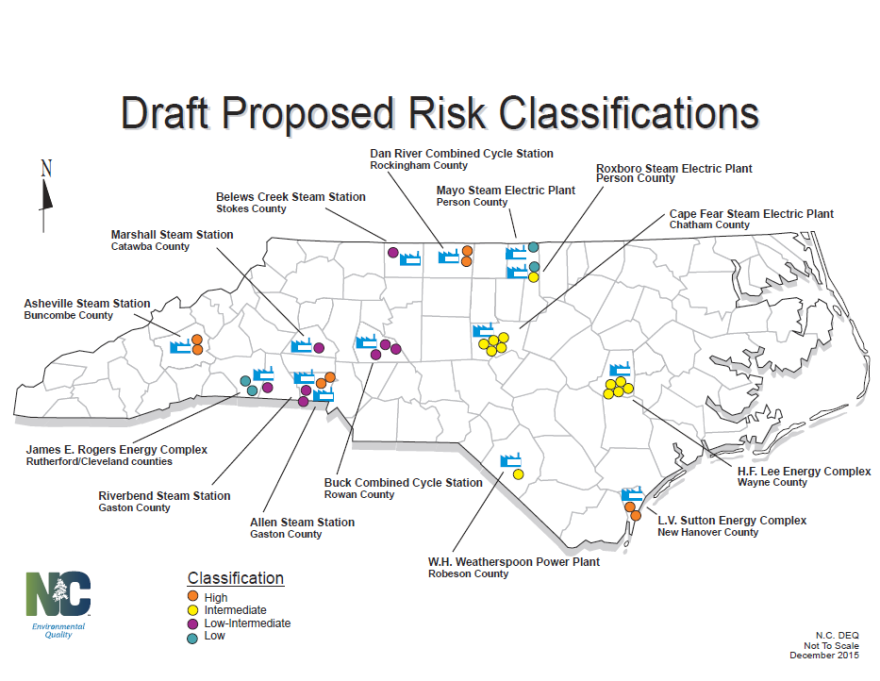

The tussle over definitions reflects a broader disagreement over how Duke should deal with the millions of tons of coal ash stored at its North Carolina plants. Over the next month, regulators will be deciding whether to rate sites “high,” “intermediate” or “low risk.”

Duke already is removing ash at four plants labeled “high risk” in the 20-14 coal ash law –including Riverbend in Mount Holly.

In December, DEQ gave storage sites at four other plants “intermediate” ratings, which also requires removal. And ash at two more plants got a low risk label - it doesn’t have to be removed.

In a December announcement, DEQ Assistant Secretary Tom Reeder says low-risk sites would still be safe.

“The method of closure for low risk impoundments could vary, and will be determined by a closure plan that protects public health and the environment,” Reeder said.

Meanwhile, DEQ said it needed more information from Duke to decide between low and intermediate risk at five more plants. After public hearings and more data from Duke, that’s what regulators are deciding now.

At lower rated sites, Duke wants the option of “capping in place.” That means draining and covering coal ash ponds, and leaving the ash where it is.

“It’s all about looking at the broad environmental impact and selecting an option that will absolutely protect ground water and put safety first all while minimizing impact to the community,” Duke spokeswoman Catherine Butler said.

Plant neighbors and environmentalists are adamant: They want ash removed. Hundreds argued the point at DEQ public hearings last month. C.D. Collins takes the long view, having lived near Duke’s Allen plant in Belmont for 56 years.

“I wish you would take all that ash out and get rid of it, so we never have to worry about it again. ‘Cause if you cap it, I’m gonna still be worried because this water is going up and down with the water table,” Collins said.

DEQ hasn’t decided yet whether to require coal ash removal at Allen, the Marshall plant on Lake Norman, Buck near Salisbury and plants in Stokes and Cleveland Counties.

State officials told residents near some plants that contaminants in their wells are “naturally occurring.” Amy Brown lives near Allen, and she isn’t convinced.

“Well there’s nothing natural about a toxic, unlined, leaking coal ash pond that sits in the groundwater. Protecting the people of North Carolina should be what’s naturally occurring,” she said.

What do scientists and engineers say about the debate?

Duke asked UNC Charlotte professor John Daniels to form a National Ash Management Advisory Board, to help it plan cleanups. He doesn’t think the debate should be simply about removal versus cap in place.

“There are lots of different solutions,” he said. “And so although we describe this as a binary cap in place versus excavation, the reality is there is a litany of solutions that could be deployed.”

Daniels acknowledges that coal ash can taint groundwater. But he says at some sites, groundwater doesn’t flow toward water supplies. Where it does, he thinks a more practical solution would be provide a new water supply.

Meanwhile, he says there are arguments against removal.

“If you consider excavation then you should also consider the effects of that excavation, in terms of trucks on the road, trains on the tracks, and the additional disturbance that that all creates,” he said.

On the other side is Dennis Lemly, a retired U.S. Forest Service biologist. He advocates removal and sees problems with leaving ash where it is.

“You’re not going to be able to stop the contact of the ash with moisture, or with water, and that’s what’s going to continue to cause it to continue to contaminate the surrounding environment,” Lemly said.

And, he wonders: What if there’s a major spill, as at Duke’s Dan River plant in 2014?

Monday, April 18, is the deadline for comments on the DEQ’s risk classifications. The final classifications are due May 18.